The rise of the Chief AI Officer (CAIO) says less about AI maturity and more about organizational anxiety. Enterprises are under intense pressure to “do something” about AI, so appointing a CAIO feels decisive.

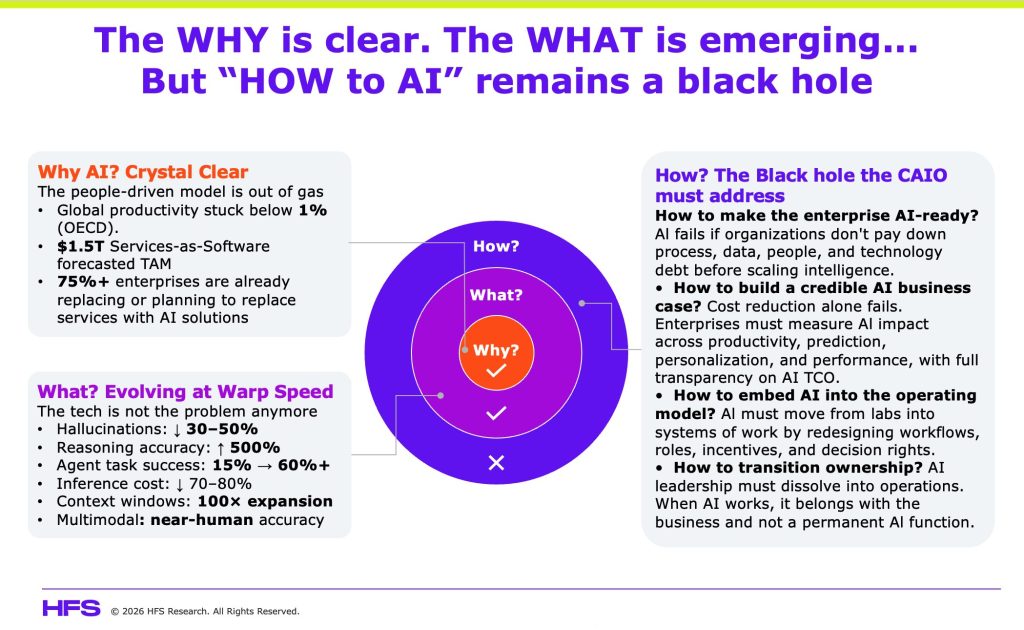

The Chief AI Officer role is no longer about why AI matters or what AI can do. The real challenge enterprises face is “how to AI.”

- How to make the enterprise AI-ready

- How to measure AI impact beyond POCs and pilots

- How to embed intelligence into the operating fabric of the business.

When appointed as a symbolic response to AI anxiety, the role becomes corporate therapy. When designed as an execution mechanism for “How to AI,” it can work:

Most CAIOs are caring experiments, not driving transformation

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: most CAIO appointments are corporate theater masking the fact that no one wants to own the mess AI creates. HFS Research data across 545 Global 2000 enterprises reveals that only 7% have achieved enterprise-wide agentic AI deployment with meaningful scale. The other 93% are stuck in various stages of pilot purgatory, burning capital while discovering the $10 trillion in accumulated enterprise debts across processes, people, data and technology are blocking effective adoption.

Even more telling, revenue per employee has increased just 1% despite heavy AI investment, while executives expect productivity improvements of 32%, better decision-making of 27%, and faster revenue growth of 26%. The gap between expectation and reality exposes the core problem: CAIOs are managing experiments, not driving transformation:

This role only works if it’s designed as a temporary forcing function to break inertia and pay down debt, not as a permanent silo that lets everyone else abdicate responsibility. If your CAIO is still relevant in three years, something fundamental has failed.

Most enterprises created the CAIO because AI exposed what was already broken, not because they had a strategy

AI doesn’t arrive as a neutral capability. It immediately exposes what HFS data shows enterprises rank as their biggest barriers: process debt (35%), data debt (19%), people debt (17%), and tech debt (16%). HFS estimates total enterprise debt at $10 trillion across Global 2000 companies, with process debt alone accounting for ~$4 trillion (see post).

The organizational barriers tell the real story, with 33% of enterprises citing “business processes not ready for agentic AI” as their primary obstacle, 31% point to “no formal governance or ownership,” and another 31% blame “lack of internal expertise.” These aren’t technology problems. These are organizational fundamentals that existed long before AI arrived.

Traditional structures can’t handle this. CIOs are buried in tech debt. CDOs are stuck in data plumbing. Business leaders want outcomes yesterday but can’t explain what success looks like. The CAIO emerges as a coordination role because AI cuts across everything and no one else wants to own the inevitable conflicts.

That’s not strategy… that’s organizational avoidance with a fancy title.

When designed properly, the CAIO breaks inertia that would otherwise paralyze transformation, but only temporarily

A viable CAIO with real authority can operationalize “How to AI”:

Create single-point accountability instead of letting every function run disconnected pilots. Someone finally has power to say “these three initiatives matter, the other seventeen are theater.”

Force alignment between ambition and reality. Executives expect 32% productivity improvement and 26% faster revenue growth, yet revenue per employee rose just 1%. The CAIO must confront this gap, forcing business leaders to explain what transformation actually means in terms of process redesign and role changes, not just pilot deployments.

Establish governance early before the first major AI failure. With 31% citing lack of formal governance and 28% pointing to regulatory concerns, someone needs enterprise authority to define and enforce “responsible AI” beyond platitudes.

Accelerate AI literacy. With 31% citing lack of internal expertise, the CAIO’s job is education and mentorship, building trust while killing magical thinking about what’s actually possible.

Kill bad pilots faster. With 93% stuck at sub-scale maturity, the CAIO should be the executioner of pilot purgatory, forcing hard decisions about what deserves investment versus innovation theater. Most AI programs fail because they celebrate activity, not outcomes. A viable CAIO replaces vanity metrics with enterprise-level measures across four Ps:

- Productivity: measurable cost takeout, throughput gains, or revenue per employee improvement

- Prediction: better forecasting, risk detection, or decision accuracy at scale

- Personalisation: differentiated customer or employee experiences driven by AI, not rules

- Performance: end-to-end business outcomes like margin, growth, cycle time, quality

Make the enterprise AI-ready. AI fails at scale not because models underperform, but because enterprises are structurally unprepared. The CAIO’s first job is to expose and pay down AI readiness debt across process, data, people and technology. The CAIO’s mandate is not to build pilots on top of this debt, but to force the organization to confront it.

Determine the true TCO of AI. Most enterprises dramatically underestimate the total cost of ownership of AI. A viable CAIO makes TCO visible by accounting for data engineering and integration costs, model lifecycle management and monitoring, human oversight and exception handling, process redesign and change management, ongoing compliance, risk, and governance. Without this transparency, AI looks cheap in pilots and expensive in production and fuels pilot purgatory.

But the moment the CAIO starts building an empire instead of dissolving into the operating model, the role has failed.

The cons are severe: figureheads, pilot factories, and permanent silos

AI becomes “someone else’s job.” The CFO stops thinking about how AI changes finance because “that’s the CAIO’s problem.” This is organizational abdication masquerading as clarity.

It turns into a pilot factory avoiding hard work. Only 22% of agentic AI initiatives are deployed in operations, the core of most businesses. CAIOs choose easier peripheral use cases over uncomfortable core workflow redesign. Impressive demos for board meetings. No observable business outcomes.

It weakens existing leaders. If the CIO, COO, and business heads wait for the CAIO to lead, AI never becomes embedded. The unspoken message: “AI isn’t my job to figure out.”

It becomes permanent instead of temporary. If the CAIO is still growing their team in year three, they’ve failed at making AI everyone’s responsibility.

It optimizes for AI success, not business success. When AI has its own executive owner, success quietly shifts toward AI metrics like models deployed, pilots launched, AI maturity scores improved. The enterprise celebrates progress in AI while productivity, margins, and revenue per employee barely move. Intelligence becomes activity, not leverage.

It accelerates AI sprawl. Without reshaping enterprise architecture, CAIO-led experimentation often adds new platforms, tools, and integrations on top of already brittle systems. AI sprawl becomes the next wave of technical debt, constraining autonomy and making scale harder, not easier.

It delays operating model redesign. The CAIO can unintentionally postpone the hardest decisions: redefining roles, incentives, and decision rights. As long as AI “belongs” to the CAIO, the organization avoids confronting how work actually changes.

The worst outcome? The CAIO becomes a scapegoat when transformation stalls instead of executives confronting that the real problem was leadership debt and organizational resistance.

Reporting structure determines authority. The CAIO must report to the CEO or COO

If the CAIO reports into IT, the role becomes too technical. Into data, too narrow. Into innovation, pure theater.

The CAIO must report to the CEO or COO. AI is an operating model issue, not a tooling decision. Without CEO-level authority, the CAIO becomes a coordinator with no power to coordinate. They can identify that 33% cite “business processes not ready” as their primary barrier, but they can’t force the redesign to fix it.

As AI matures, the role should dissolve into functional leadership. The CFO owns AI in finance. The Chief Revenue Officer owns AI in sales. That’s when transformation succeeded.

Without real authority to say “no,” the CAIO becomes decorative

A viable CAIO must be able to:

Stop initiatives that don’t align to strategy. With 93% stuck in pilot purgatory and only 22% of initiatives in core operations, the power to say “no” is more important than saying “yes.”

Set enterprise standards. With 38% citing poor data quality and 31% pointing to lack of governance, no more bespoke experimentation where every function ignores standards because “our use case is different.”

Force uncomfortable conversations about process redesign. With 33% citing “business processes not ready,” the CAIO must tell business leaders “your process is the problem, not the technology,” and have authority to drive redesign when politically uncomfortable.

Tie investments to measurable outcomes. Executives expect 32% productivity improvement and 26% faster revenue growth. Revenue per employee rose 1%. That disconnect is the CAIO’s problem to solve. No more celebrating models deployed. Did revenue increase? Did costs decline? If not, kill the initiative.

Without these powers, you’ve created an expensive observer with no ability to drive change.

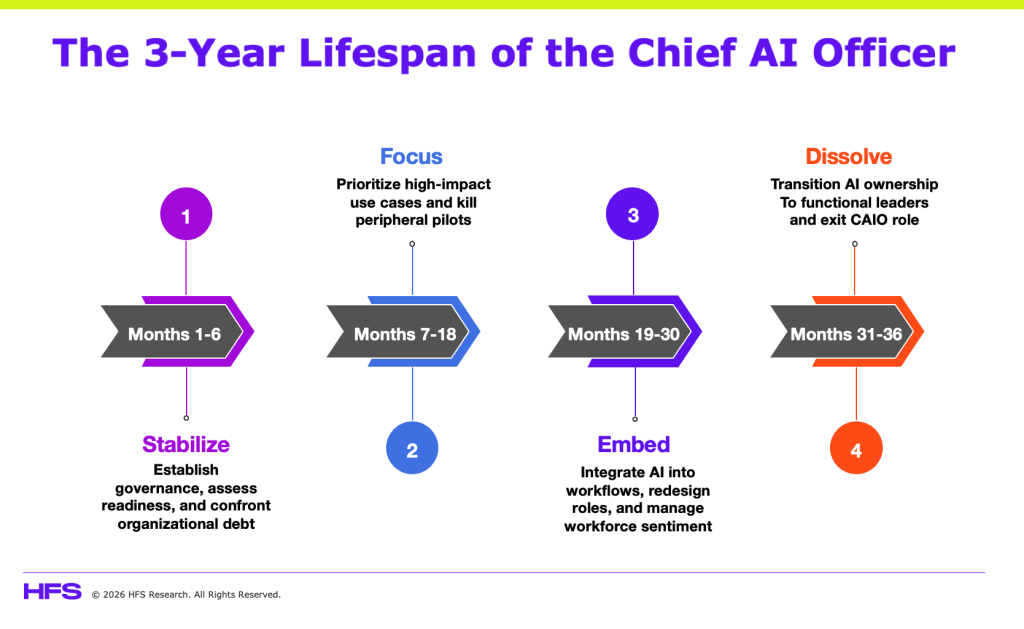

The right pacing is stabilize, focus, embed, dissolve. Most CAIOs get stuck at pilot and never reach production

Phase 1: Stabilize (Months 1-6) Establish guardrails, governance, and AI literacy before launching initiatives. Expose where the organization is not ready: the $10 trillion in process debt, data debt, leadership debt, and tech debt that will kill transformation if ignored.

Phase 1: Stabilize (Months 1-6) Establish guardrails, governance, and AI literacy before launching initiatives. Expose where the organization is not ready: the $10 trillion in process debt, data debt, leadership debt, and tech debt that will kill transformation if ignored.

HFS data shows enterprises rank challenges in this order: process inefficiencies (35%), data limitations (19%), people challenges (17%), technology constraints (16%). With 31% citing lack of formal governance and another 31% pointing to lack of internal expertise, force executives to confront that their enthusiasm for AI doesn’t match their willingness to fix what’s broken. With only 7% of enterprises at pioneering scale, most organizations massively overestimate their readiness.

Phase 2: Focus (Months 7-18) Concentrate on a small number of high-impact use cases tied to core workflows, not peripheral nice-to-haves. Kill the other pilots. HFS found two-thirds of enterprises stuck in low-complexity, assistive deployments: recommendation agents, task automation bots, copilots. Only 22% of agentic AI initiatives are deployed in operations, the actual core of the business.

Force business leaders to choose the three initiatives that actually matter instead of running seventeen experiments that never reach production. Measure outcomes, not activity. When executives expect 32% productivity improvement and 26% faster revenue growth but revenue per employee rose just 1%, someone needs to demand accountability.

Phase 3: Embed (Months 19-30) Move AI out of labs and into systems of work. Redesign processes, roles, and incentives to reflect the new operating model. This is where most transformations stall because embedding requires uncomfortable conversations about whose job changes, who reports to whom, and what skills matter going forward.

HFS data shows 78% of organizations operating at low autonomy levels for agentic AI: 14% with no autonomy, 34% at assisted execution, 29% at supervised autonomy. Only 10% have reached broad autonomy where AI agents operate across multiple domains with minimal human intervention. You can’t execute transformation when most of your AI still requires constant human oversight. The CAIO must shift the organization from experimentation to production deployment, from supervised pilots to autonomous operations at scale.

Phase 4: Dissolve (Months 31-36) As AI becomes business as usual, the CAIO’s remit should shrink, not expand. Authority moves to functional leaders. The CFO owns AI in finance. The Chief Revenue Officer owns AI in sales. The CAIO transitions from executor to advisor, then exits. The endgame is not an AI-first function. It’s an AI-native enterprise where every leader owns their domain’s AI integration.

The biggest mistake is moving too fast in Phase 1-2 (launching pilots before governance exists) or too slow in Phase 3-4 (staying comfortable in experiment mode instead of forcing production deployment and organizational redesign).

Most CAIOs get stuck running permanent pilot factories in Phase 2 because Phase 3 requires political capital they don’t have and Phase 4 requires admitting their job should disappear.

The real measure of CAIO success is how quickly the role becomes irrelevant, not how powerful it becomes

The CAIO works best as a catalyst. A forcing function. A temporary concentration of authority to break inertia, pay down organizational debt, and rewire decision-making that existing structures couldn’t handle.

If the CAIO becomes permanent, something else has failed. Either:

- The organization never actually committed to transformation and the CAIO became a scapegoat absorbing responsibility without authority

- The CAIO built an empire instead of embedding AI into functional leadership

- Leadership debt was so severe that no temporary role could fix it, revealing deeper dysfunction

HFS data across 545 enterprises shows the scale of the challenge: 93% stuck at sub-scale maturity, 78% operating at low autonomy levels, only 10% achieving broad autonomy, only 22% of initiatives deployed in core operations, and business processes ranked as the #1 barrier (33%) ahead of technology. These aren’t problems a permanent CAIO solves. These are organizational fundamentals that require every leader taking ownership.

The endgame is not an AI-first function. It is an AI-native operating model. Enterprises should stop looking at AI as a digital capability. It is an operating fabric:

- It reshapes how work flows

- How decisions are made

- How performance is measured

- How humans and machines interact at scale

These are operating model responsibilities. When AI is working, it belongs with the business, not one entity.

The uncomfortable question enterprises need to confront: are you appointing a CAIO because you have a clear transformation plan that requires temporary concentrated authority, or because “everyone else is doing it” and you need to look like you’re taking AI seriously? The first creates value. The second creates theater.

Bottom line: Stop appointing Chief AI Officers as corporate therapy: the role only works when it is designed to disappear

Only appoint a Chief AI Officer if you’re committed to giving them COO/CEO-level authority to kill initiatives, force standards, and drive uncomfortable organizational change, and only if you’re prepared for the role to disappear within 36 months as AI embeds into every functional leader’s responsibility. HFS data shows 93% of enterprises struggling to move agentic pilots to production, 78% operating at low agentic autonomy levels, only 10% achieving broad autonomy, and revenue per employee from tech services up just 1%. Meanwhile, we saw 32% growth in AI investments in 2025… the expectations are ramped up for 2026, and the need for an empowered, focused CAIO is front and center.

However, if your CAIO is still building their team in year three, they’ve failed at making AI everyone’s job. The role exists to break inertia and pay down debt, not to create a permanent silo that lets other executives abdicate ownership. Ask yourself honestly: are you creating a CAIO because you have a transformation strategy that requires concentrated authority, or because appointing someone feels decisive while avoiding the harder question of why your existing leaders can’t integrate AI into their domains? The answer determines whether you’re solving organizational anxiety or just creating expensive theater with a fancy title.

Posted in : Agentic AI, AGI, Artificial Intelligence, Automation, GenAI, LLMs, OneOffice